|

| Remains in the larnax of the main chamber. Photo: Vergina: The Royal Tombs (Andronikos, 1984) |

In 1977, Manolis Andronikos discovered a cluster of Temenid burials at Vergina, ancient Aegae, under the Great Tumulus. Tomb II was unlooted, doublé chambered and each chamber had a sarcophagus housing a gold larnax (casket) that contained the cremated bones of a man and a woman, respectively. The king’s body was cremated in a great pyre, in the same way as epic heroes of the Iliad. A huge pile of half-burnt mud bricks, ashes, charcoal, and hundreds of burnt objects covered the whole length of the tomb’s barrel-vaulted roof. The presence of this pyre was the clearest evidence that the ΣΥΝΕΧΙΣΤΕ ΤΗΝ ΑΝΑΓΝΩΣΗ

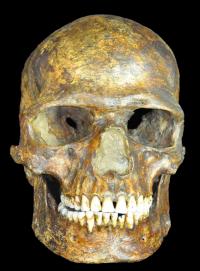

COPENHAGEN, DENMARK—DNA from the ulna of a modern human skeleton discovered in 1954 at an archaeological site at Kostenki-Borshchevo, located in southwest Russia, has been mapped by a team of scientists led by evolutionary biologist Eske Wilerslev of the Natural History Museum at the University of Copenhagen. The skeleton has been dated to between 36,200 and 38,700 years old, making the genome the second oldest to be sequenced. This new data suggests that this man, who had dark skin and dark eyes, had DNA from Europe’s indigenous hunter-gatherers, people from the Middle East who later became early farmers, and western Asians. It had been thought that these three groups only mixed in the past 5,000 years. “What is surprising is this guy represents one of the earliest Europeans, but at the same time he basically contains all the genetic components that you find in contemporary Europeans—at 37,000 years ago,” Willerslev told

COPENHAGEN, DENMARK—DNA from the ulna of a modern human skeleton discovered in 1954 at an archaeological site at Kostenki-Borshchevo, located in southwest Russia, has been mapped by a team of scientists led by evolutionary biologist Eske Wilerslev of the Natural History Museum at the University of Copenhagen. The skeleton has been dated to between 36,200 and 38,700 years old, making the genome the second oldest to be sequenced. This new data suggests that this man, who had dark skin and dark eyes, had DNA from Europe’s indigenous hunter-gatherers, people from the Middle East who later became early farmers, and western Asians. It had been thought that these three groups only mixed in the past 5,000 years. “What is surprising is this guy represents one of the earliest Europeans, but at the same time he basically contains all the genetic components that you find in contemporary Europeans—at 37,000 years ago,” Willerslev told