Intriguing enigmas continue to envelop the story of the Amphipolis tomb. What was the gender of the occupant? When was the tomb sealed? Who was the architect of the monument? What event do the paintings depict? This article unravels them all.

What was the gender of the occupant?

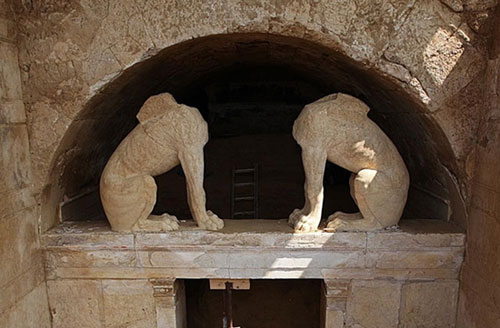

There is an excellent chance that this question will be answered conclusively some time in the coming months through the promised laboratory investigation of the skeleton. However, Katerina Peristeri, head of the excavation, confirmed at the Ministry of Culture presentations on 29th November that nobody currently has any idea of the skeleton’s gender, because the bones were too fragmented for the archaeologists to be able to check the features that determine gender and because the remains were collected with the surrounding soil still partially encasing them in order best to preserve the evidence for the laboratory investigation. Nevertheless, she repeated her previous opinion that the occupant is most likely a male and one of Alexander’s generals based on the fact that the Amphipolis lion that once stood atop the mound is male and its base was decorated with shields.

This idea is not new, but has been the standard theory of scholars ever since the fragments of the lion monument were rediscovered more than a century ago. Parts of the shields can clearly be seen on some of the blocks now stored near the reconstructed lion monument near Amphipolis (Figure 1).

|

| Fig. 1. A block with part of a shield from the lion monument that once crowned the Kasta Mound |

But is it true that a monument with a male lion and shields necessarily commemorates a man? In the period of the Amphipolis tomb it happened that two royal women took a leading role in warfare. Firstly, Adea-Eurydike, who was a granddaughter of Alexander’s father, Philip, became the queen in 321BC by marrying PhilipArrhidaeus, the mentally retarded half-brother of Alexander, whom the troops had elected to the monarchy in Babylon on Alexander’s death. In 317BC Adea tried to win precedence for her husband over the official joint-king, Alexander IV, Alexander the Great’s 6-year-old son. This prompted Alexander IV’s grandmother, Olympias, to lead her nephew Aeacides’ army across the mountains from Epirus into Macedonia to defend her grandson’s rights. Athenaeus 560f describes the situation: “The first war waged between two women was that waged between Olympias and Adea-Eurydike, during which Olympias dressed rather like a Bacchant, to the accompaniment of tambourines, whereas Adea-Eurydike was armed from head to toe in Macedonian fashion, having been trained in military activities by Kynna, the princess from Illyria [and a wife of Philip II].” Olympias was victorious and received the epithet Stratonike, which mean’s “the army’s victory goddess”. A monument with shields would be entirely appropriate for either of these queens.

Olympias also had a claim to the lion as a personal badge as Plutarch, Life of Alexander 2.2 records: “After their marriage, Philip dreamt that he was putting a seal upon Olympias’s womb, and the device of the seal, as he imagined, was the figure of a lion. The other seers were led to suspect that Philip needed to keep a closer watch upon his marriage relations; but Aristander of Telmessus said that the woman was pregnant, since a seal was not put on that which was empty, and pregnant with a son whose nature would be bold and lion-like.”

|

| Fig. 2. A tetradrachm of Alexander’s general Ptolemy minted in ~310BC with Athena bearing a shield and wielding a spear |

Coins minted by Macedonians at that time also bear witness to the new phenomenon of warrior women. In Egypt, Alexander’s former general, Ptolemy, minted a series of silver tetradrachms with an image of the deified Alexander wearing an elephant scalp on the obverse and a representation of the goddess Athena bearing a shield and wielding a spear on its reverse (Figure 2). It is even possible that Ptolemy introduced this reverse to recognise the battle between the queens in his homeland of Macedon, because it first appeared within a year or two of that event. Though not properly a goddess like Athena, Olympias was the mother of a fully-fledged god at the time of her death: for example, the deified Alexander on the coins of Ptolemy was introduced in about 321BC. Furthermore, Alexander himself was recorded to have wished to make his mother a goddess after her death (Curtius 9.6.26-27). Finally, the epithet Olympias by which we know the queen was not her original name (that was probably Polyxena, although she was also later called Myrtale), but an honorific title meaning “one of the goddesses from Mount Olympus” awarded to her by King Philip at about the time that she gave birth to Alexander.

|

| Fig. 3. Warrior weapons in the antechamber of the tomb of Philip II presumed to be the property of the queen buried within the same room. |

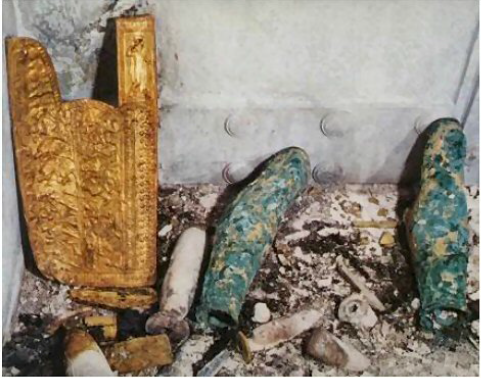

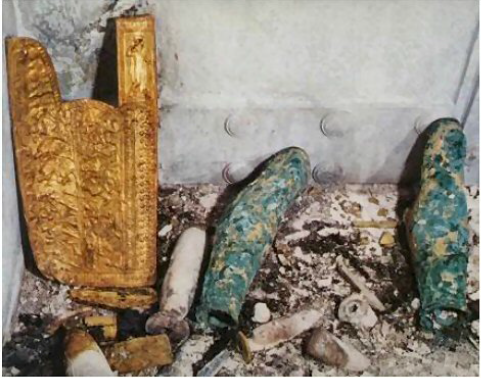

Furthermore, one of Philip’s wives, perhaps Meda, was buried in the antechamber of his tomb at Aegae-Vergina. Historians now believe that the arms found in the antechamber belonged to this queen rather than to Philip. They included a golden gorytus (arrow quiver) and greaves (lower leg armour) – see Figure 3.

It should also be emphasised that all the symbolic decorations within the actual tomb chambers at Amphipolis are unambiguously female in character: the sphinxes, the caryatids/klodones and the figure of Persephone in the mosaic.

For all these reasons, it would not be surprising for a Macedonian queen and Olympias in particular to be commemorated by the lion monument decorated with warrior shields atop the mound at Amphipolis. It is therefore especially interesting that we learnt from Katerina Peristeri at the presentations on Saturday 29th November that she had partly been inspired to dig the Kasta Mound by stories from the local people that it was the tomb of a famous queen. Sometimes such legends harbour a germ of truth.

|

| Fig. 4. An empty sarcophagus kept next to the stones salvaged from the lion monument at Amphipolis |

There is also another tantalising possibility: that one of Alexander’s generals actually was entombed within the lion monument itself in addition to the tomb beneath the mound. There is one obvious candidate. One of Alexander’s eight somatophylakes, the king’s most senior staff officers, a Macedonian named Aristonous, who was the commander of Olympias’s army in her war with Cassander and was also the muchloved lord of Amphipolis. But Cassander arranged his murder at about the same time that he had Olympias killed. One intriguing observation is that a sarcophagus is kept amongst the group of stones salvaged from the lion monument stored next to the current partially reconstructed lion (Figure 4). I have no confirmation at present whether it is indeed itself from the monument, but it certainly merits future investigation.

When was the tomb sealed?

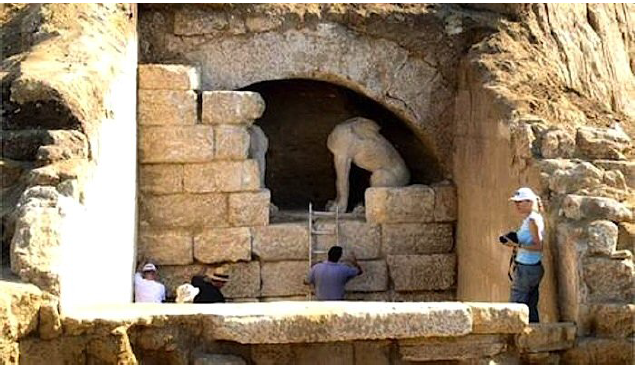

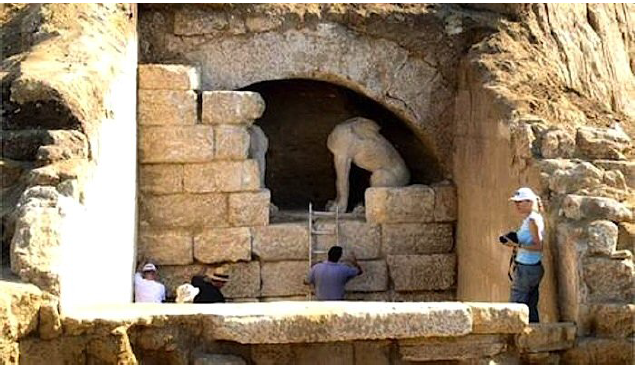

Understanding the history of the tomb at Amphipolis depends critically on determining when and by whom the intensive sealing operation was conducted. Sealing walls of massive, unmortared blocks seemingly taken from the peribolos wall were erected in front of both the caryatids and in front of the sphinxes and all three of the chambers within were sedulously filled with sand dredged from the bed of the nearby River Strymon. It was confirmed in the presentations of 29th November that the holes in the masonry near the level of the arched ceiling were used to carry sand into the interior after the sealing walls had been erected and were not made by looters.

However, the most intriguing statement made on 29th November was by architect Michael Lefantzis, who is reported to have said that the sealing walls were made and the backfilling was done in the Roman era, whilst also confirming that the sealing walls were manufactured from material removed from another part of the monument.

|

| Fig- 5. Ancient paint on the capital of a pilaster in the façade beneath the sphinxes |

The archaeologists also said that the tomb was open to visitors for some time and a Roman sealing might be taken to imply that visits to the tomb took place for at least several centuries. However, the archaeologists and the Ministry of Culture have previously published some evidence, mainly photographic, that could suggest that the tomb was only open for a relatively short period before being closed up:

1) Ancient paint survives on the façade, for example on the capitals of the pilasters either side of the portal beneath the sphinxes (Figure 5). Preferential weathering of exterior paint should be expected and centuries of weathering would normally completely remove paint, but the paint on the façade is in no worse condition than the paint within the first chamber.

|

| Fig. 6. Blocks in the sealing wall erected in front of the portal of the sphinxes during their removal showing that the blocks were not mortared together |

2) The masonry in the sealing walls was not mortared, but the stones were merely stacked on top of one another (Figure 6). This was normal in the Hellenistic period, but the Romans nearly always used mortar between the stones in their walls.

3) There are ancient steps in a couple of the released photos (e.g. Figure 7): although there is some chipping to the edges of these steps, they are nevertheless still sharp, crisp and flat in some central parts of their edges. Over centuries a smooth pattern of wear should be expected.

|

| Fig. 7. Flooring of marble fragments in red cement without apparent wear and an ancient step with parts of its edge still sharp and unworn. |

4) Neither the paving in the first chamber (Figure 7) nor the mosaic in the second chamber (Figure 8) shows any sign of the differential wearing to the areas where visitors would predominantly have trodden (the damage to the centre of the mosaic must have been due to an event at the time of sealing or only just before, since it is reported that loose pieces were found still in place during the excavation.)

|

| Fig. 8. The section of the Persephone mosaic adjoining the entrance to the second chamber exhibits little sign of wear |

There may be answers to some of these points: e.g. it has been suggested that the entrance might have had a roof over it (although that would have made the interior of chamber 2 very dark). However, collectively there is an implication from these points that the tomb chambers may not have been open to visitors for as long as centuries.

The other difficulty with a Roman era sealing is the question of motive. It will have been expensive and time-consuming to build the sealing walls and to dredge and transport thousands of tonnes of sand. Also, since there were no grave goods left, the only thing of possible value inside the tomb was the bones themselves. Yet these bones were left scattered about in and out of the grave slot. If the sealer was concerned to protect the bones, why did he/she not tidy them up before sealing the tomb?

An easy way to remove doubt on the sealing date would be to announce Roman dating evidence found within the sealing wall erected in front of the sphinxes. In fact Katerina Peristeri said on November 29th that there were no potsherds or coins in the main chamber, but that the archaeologists found a lot in other areas: “In the main chamber we do not have any grave goods. They have been taken away or maybe they were somewhere else. The geo-survey that we are doing may give us more info about what there might be elsewhere, but in the other areas (χωροι) we have pottery and coins that are being cleaned and studied. We simply haven’t shown them to you. The dating is in the last quarter of the fourth century B.C in one phase and we have coins from the 2nd century B.C, which is the era of the last Macedonians to protect their monument and from the Roman years from the 3rd century A.D.” Unfortunately, this remains ambiguous on the question of whether any of this evidence was found within the sealing wall erected in front of the sphinxes.

Consequently, the key question now is: what is the latest attributable date of anything datable found inside the sealing wall erected in front of the sphinxes? In general, the latest datable material is likely to be a good indication of when the tomb was finally sealed. If anything definitely Roman has been found inside that wall, then the final sealing was very probably Roman. In that case the parallel evidence that the tomb has only been lightly visited may imply that the sealing history is fairly complex, perhaps involving an early sealing, a later opening and a final re-sealing.

Who was the architect of the monument?

The archaeological team at the Amphipolis tomb have previously speculated about the identity of its architect and in their presentations on Saturday 29th November they confirmed that the whole monument was the work of a single architect with the exception of the cist grave and its slot, which is now confirmed to pre-date the rest of the monument. I am confident that the archaeologists are right on these points.

|

| Fig. 9. The proposal of Deinocrates to Alexander to carve Mt Athos into his image |

The most interesting name that the archaeologists have put forward in connection with the identity of the tomb’s designer is that of Alexander’s architect, Deinocrates (literally the “Master of Marvels”). He is widely referenced in the ancient sources and is also called Cheirocrates (“Hand Master”), Stasicrates, Deinochares and even Diocles. It has been suggested that Stasicrates was his real name and that Deinocrates was a nickname. He was the proposer of the project to sculpt Mount Athos into a giant statue of Alexander, although this was rejected by the king (see Figure 9). He is specified to have restored the temple of Artemis at Ephesus and Plutarch (Alexander 72.3) writes that Alexander “longed for Stasicrates” for the design and construction of Hephaistion’s pyre and monument. Most famously of all, Deinocrates was Alexander’s architect for Alexandria in Egypt. In my book, The Quest for the Tomb of Alexander the Great, 2nd Edition, 2012, p.160, I made a link between the masonry of the most ancient fragments of the walls of Alexandria and the Lion Tomb at Amphipolis (i.e. the blocks from the structure that supported the lion, which was all that was known at that time):

“The blocks of limestone in the oldest parts of this fragment [of the walls of ancient Alexandria, located in the modern Shallalat Gardens] are crammed with shell fossils and the largest stones are over a metre wide, although they vary in size and proportions. They have a distinctive band of drafting around their edges, but the remainder of the face of each was left rough-cut. The Tower of the Romans in Alexandria was faced with the same style of blocks, including the bands of drafting.

Such blocks are particularly to be found in the context of high status early-Hellenistic architecture. Pertinent examples elsewhere include the blocks lining the Lion Tomb at Knidos and the original base blocks of another Lion Tomb from Amphipolis in Macedonia. Both most probably date to around the end of the fourth century BC and are best associated with Alexander’s immediate Successors.”

|

| Fig. 10. Oldest remaining fragment of the walls of Alexandria (above) showing the same band of drafting around the edges of the blocks as the blocks in the peribolos wall of the Amphipolis mound (below). |

The blocks from the oldest surviving part of the walls of Alexandria are also comparable with the blocks in the peribolos wall now uncovered at Amphipolis. Both have the distinctive band of drafting around the block edges with the stones being left rough-cut in their central reservations (Figure 10).

|

| Fig. 11. The map of ancient Alexandria based on excavations in 1865 by Mahmoud Bey. |

The archaeologists have put forward one slightly complicated argument in favour of Deinocrates having built the Amphipolis tomb based on a map of ancient Alexandria (Figure 11) drawn by Mahmoud Bey in 1866 following his extensive excavations across the site of the ancient city performed in 1865. Mahmoud reconstructed the street grid based on results at numerous dig sites. He inferred the size of a stade, the standard Greek measure of large distances, to have been 165m in Alexandria by noting that the separations of the roads in the street grid were fixed numbers of stades.

He also reconstructed the course of the ancient city walls on the basis of excavations on the eastern and southern sides, but in the west and to some extent on the northern side he had to guess their course in many places, due to modern developments having made the necessary excavation sites inaccessible. He came up with an overall perimeter for the walls of 96 Alexandrian stades or 15.84km (although Mahmoud himself actually wrote “around 15,800m” in his book.)

The Amphipolis archaeologists noticed that the Alexandrian wall circuit of Mahmoud Bey, which they supposed to have been planned by Deinocrates, is almost exactly one hundred times the diameter of the Kasta Mound as defined by its circular peribolos wall, which they have measured at 158.4m. They have suggested that this coincidence suggests that Deinocrates was the architect for the Amphipolis tomb as well as for Alexandria.

However, there are a few difficulties with this hypothesis:

1) There are three ancient writers that give the perimeter of Alexandria’s walls: Curtius at 80 stades, Pliny at 15 miles and Stephanus Byzantinus at 110 stades. All of these are significantly different to the modern 15.84km value from Mahmoud Bey.

2) It is doubtful whether all of Mahmoud’s wall line, especially in the west, can be accurate, since he did not actually find any definite traces of the wall over large stretches of his reconstructed perimeter.

3) It is doubtful whether the outer wall mapped by Mahmoud Bey was part of Deinocrates’ original plan for Alexandria. It is essentially the wall line of the city at its zenith around the time of Augustus. It is unlikely that Alexander founded the town to be 5km wide, so that it would have needed half a million inhabitants to fill it. The only fragment surviving now of early Ptolemaic wall is in the line of a much smaller circuit, near the middle of Mahmoud’s city and encompassing its central crossroads. That is a better candidate for Deinocrates’ handiwork.

4) To compare a perimeter with a diameter is not comparing like with like. It is the unit of large-scale measurement, the stade, which should really be compared between Alexandria and the Kasta Mound of the Amphipolis tomb.

Usually in Greek cities the stade was defined as measuring 600 feet. So for, example, in Athens a stade was 185m. However, Alexander the Great employed men called bematists (literally “pacers”) to measure the distances between the towns and cities that he passed through on his campaigns. We still have some of the lists of towns and the distances between them as measured by Alexander’s bematists (known as the stathmoi or “stages”). Since many of the places in these lists have known locations today it is possible to calculate from modern maps how long the stade used by Alexander’s bematists must have been and the answer is 157m (see Fred Hoyle, Astronomy, Rathbone Books Limited, London 1962.) That would require a foot of only 26cm, which would be extraordinarily small and well below the normal range. But it would of course have been impractical for the bematists to measure distances of hundreds of km between cities by putting their feet down heel to toe repeatedly, so they must have used paces instead of feet to define their stade. In fact we know that a Roman mile was defined as 1000 paces and that is 1481m, so it is likely that Alexander’s bematists were using a stade of 100 paces (of two steps per pace). Anyway, it is clear that the diameter of the Kasta Mound at Amphipolis is actually remarkably close to the stade used by Alexander’s bematists. And actually the Alexandrian stade of 165m is closer to the bematists’ stade than to the 600-foot stade of other cities. The conclusion could be that the architect of Alexandria and the architect of the Amphipolis tomb both paced out their plans in a fashion similar to Alexander’s bematists. So there is a slight link after all between Deinocrates, the known architect of Alexandria, and the architect of the Amphipolis tomb.

Furthermore, Deinocrates is associated with projects that were intended to impress through extraordinary size, so that is another good reason to consider Deinocrates to be a candidate in the case of the Kasta Mound. We can certainly say that an illustrious Greek architect designed the Kasta Mound and its Lion Tomb with a 100 pace diameter in order deliberately to impress through size and through a planned size of exactly one of Alexander’s bematists’ stades.

Deinocrates therefore remains a good candidate for the identity of the architect of the Amphipolis lion tomb. However, the evidence is largely circumstantial and it relies in particular on the correctness of the dating of the tomb to the last quarter of the 4th century BC. I see no reason to doubt this dating and the archaeologists invoked the style and execution of the mosaic in their presentations on 29th November to bolster the case for their late 4th century BC date. However, we will need to see a bit more dating evidence to be absolutely confident in assigning the tomb to a narrow quarter century time slot.

|

| Fig. 12. A man and a woman wearing red belts dancing either side of a bull in a painting from the burial chamber of the Amphipolis tomb |

What event do the paintings depict?

The Greek Ministry of Culture published photos of the paintings recently found decorating the architraves in the third (burial) chamber of the Amphipolis tomb on 3rd December 2014. They depict a man and a woman wearing red belts or sashes around their waists dancing either side of a bull (Figure 12) and a winged woman between a tall urn and a cauldron or brazier on a tripod (Figure 13). The press release also mentions that the marble roof beams in the chamber were painted with rosettes.

|

| Fig. 14. A winged woman between a large urn and a brazier on a tall tripod in a painting from the burial chamber of the Amphipolis tomb |

These scenes appear to be associated with some kind of cult activity and I will show that there are significant parallels with what we know of the activities at one particular cult site: the Sanctuary of the Great Gods on Samothrace, where the Mysteries of Samothrace were conducted. This island sanctuary was long patronised by the royal family of nearby Macedon and in the era of the Amphipolis tomb, the last quarter of the 4th century BC, that patronage is particularly linked to Queen Olympias. Notably Plutarch, Alexander 2.1 writes: “We are told that Philip, after being initiated into the mysteries at Samothrace at the same time as Olympias, he himself still being a youth

and she an orphan child, fell in love with her and betrothed himself to her at once with the consent of her brother, Arymbas.”

|

| Fig. 14. Frieze with garlanded bulls’ heads and a rosette from the Arsinoe Rotunda in the Sanctuary of the Great Gods on Samothrace. |

The first connection with the mysteries of Samothrace is the combination of bull sacrifice with rosettes. There is a sculpted relief from the early 3rd century BC Arsinoe Rotunda at the sanctuary on Samothrace, which depicts two garlanded bulls’ heads either side of a large 8-petal rosette (Figure 14). It has been assumed that it alludes to bull sacrifices during the mysteries. In fact it is known that a section of the ceremonies involved animal sacrifices and it is certain that this included bull sacrifices in the Roman period. It is therefore quite striking that the newly discovered paintings depict a possible bull sacrifice in the context of a chamber also decorated with similar rosettes.

|

| Fig. 15. The Victory of Samothrace from the Sanctuary of the Great Gods |

The second connection derives from the very strong association of the Sanctuary on Samothrace with Nike, the winged goddess of victory. Most famously, the wonderful “Victory of Samothrace”, now in the Louvre (Figure 15), was discovered in pieces around one of the ruined temple buildings in the Sanctuary of the Great Gods by Charles Champoiseau in March 1863. Additionally there is a votive stele dedicated to the Great Gods of the Samothrace Sanctuary found at Larissa in Thessaly by the

Heuzey and Daumet expedition (Figure 16) and that too depicts the goddess Nike as a central part of its composition. A winged woman in Greek art of the early Hellenistic period is usually a depiction of Nike, so we can reasonably assume that the winged woman in the newly discovered paintings is also the goddess of victory.

|

| Fig. 16. A stele found at Larissa dedicated to the Great Gods of Samothrace including a central depiction of the winged goddess Nike |

It is known as well that some of the ceremonies for the mysteries of Samothrace took place at night. A foundation was recovered at the Hieron within the Samothrace Sanctuary, which could have supported a giant torch, but maybe something like the tall brazier in the newly discovered paintings could have fulfilled the function of illuminating nocturnal ceremonies. More generally, the discovery of numerous lamps and torch supports throughout the Sanctuary of the Great Gods confirms the nocturnal nature of the initiation rites. Furthermore, it is suspected that initiates at Samothrace were promised a happy afterlife, as was also the case in the mysteries conducted at Eleusis near Athens. This would make scenes from the mysteries of Samothrace an excellent subject for decoration of an initiate’s tomb.

Finally, and perhaps most strikingly of all, we know from ancient reports (e.g. Varro’s Divine Antiquities) that a particular feature of the mysteries at Samothrace was that initiates wore red sashes around their waists. It is therefore rather noteworthy to see just such red sashes around the waists of the man and woman dancing either side of the bull in the newly discovered paintings from the burial chamber at Amphipolis.

If these associations between the burial chamber paintings and the mysteries at Samothrace are true, then this provides another strong indication that the occupant of the Amphipolis tomb could be Olympias, the mother of Alexander the Great.

Author

Andrew Chugg