Excavation of the third chamber of the Kasta Tumulus in Amphipolis has revealed a limestone cyst grave containing human remains 1.6 meters (5’2″) beneath the surviving floor stones. The grave is 3.23 meters (10’7″) long, 1.56 meters (5’1″) wide and one meter (3’3″) high, but uprights discovered when the cyst was excavated indicate the walls were original at least 1.8 meters (5’10″) high. Two of the limestone slabs that once covered the grave are missing, and bones were found both inside and outside the grave, evidence the tomb was interfered with by looters in antiquity.

Excavation of the third chamber of the Kasta Tumulus in Amphipolis has revealed a limestone cyst grave containing human remains 1.6 meters (5’2″) beneath the surviving floor stones. The grave is 3.23 meters (10’7″) long, 1.56 meters (5’1″) wide and one meter (3’3″) high, but uprights discovered when the cyst was excavated indicate the walls were original at least 1.8 meters (5’10″) high. Two of the limestone slabs that once covered the grave are missing, and bones were found both inside and outside the grave, evidence the tomb was interfered with by looters in antiquity.

When the soil filling the grave was removed, archaeologists found a little ledge going around the bottom inside perimeter. A wooden coffin was originally placed on that ledge. It has long since rotted away, but iron and copper nails from the coffin were found scattered, as were ivory and glass decorations that once adorned it.

When the soil filling the grave was removed, archaeologists found a little ledge going around the bottom inside perimeter. A wooden coffin was originally placed on that ledge. It has long since rotted away, but iron and copper nails from the coffin were found scattered, as were ivory and glass decorations that once adorned it.

The bones have been removed and will be studied in the lab. The hope is that they will be able to tell us something about the identity of the tomb’s owner. It’s going to be a tall order. Even determining sex from disarticulated bone pieces is a challenge that could well be insurmountable.

The bones have been removed and will be studied in the lab. The hope is that they will be able to tell us something about the identity of the tomb’s owner. It’s going to be a tall order. Even determining sex from disarticulated bone pieces is a challenge that could well be insurmountable.

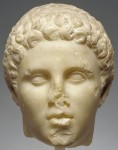

The always excellent Dorothy King of PhDiva posits that if the remains prove to be male, a likely candidate for the occupant of this tomb is Hephaestion, Alexander’s the Great’s closest friend from childhood who was worshipped as a divine hero after his premature death from a fever in 324 B.C. Alexander was devastated by the loss of Hephaestion, likening their relationship to that of Achilles and Patroclos of Trojan War fame and explicitly modeling his mourning after Achilles’.

The always excellent Dorothy King of PhDiva posits that if the remains prove to be male, a likely candidate for the occupant of this tomb is Hephaestion, Alexander’s the Great’s closest friend from childhood who was worshipped as a divine hero after his premature death from a fever in 324 B.C. Alexander was devastated by the loss of Hephaestion, likening their relationship to that of Achilles and Patroclos of Trojan War fame and explicitly modeling his mourning after Achilles’.

Plutarch describes Alexander’s reaction to Hephaestion’s death in Parallel Lives:

Alexander’s grief at this loss knew no bounds. He immediately ordered that the manes and tails of all horses and mules should be shorn in token of mourning, and took away the battlements of the cities round about; he also crucified the wretched physician, and put a stop to the sound of flutes and every kind of music in the camp for a long time, until an oracular response from Ammon came bidding him honour Hephaestion as a hero and sacrifice to him. Moreover, making war a solace for his grief, he went forth to hunt and track down men, as it were, and overwhelmed the nation of the Cossaeans, slaughtering them all from the youth upwards. This was called an offering to the shade of Hephaestion. Upon a tomb and obsequies for his friend, and upon their embellishments, he purposed to spend ten thousand talents, and wished that the ingenuity and novelty of the construction should surpass the expense. He therefore longed for Stasicratesa above all other artists, because in his innovations there was always promise of great magnificence, boldness, and ostentation. This man, indeed, had said to him at a former interview that of all mountains the Thracian Athos could most readily be given the form and shape of a man; if, therefore, Alexander should so order, he would make out of Mount Athos a most enduring and most conspicuous statue of the king, which in its left hand should hold a city of ten thousand inhabitants, and with its right should pour forth a river running with generous current into the sea. This project, it is true, Alexander had declined; but now he was busy devising and contriving with his artists projects far more strange and expensive than this.

So according to Plutarch Alexander had decided against turning all of Mount Athos into a sort of pre-dynamite one-man Mount Rushmore monument to himself, but he planned to make an even more elaborate tomb for his beloved companion, one worthy of a divine hero. Perhaps Alexander’s death in 323 B.C. kept the crazier of the grandiose plans from taking hold or perhaps the ancient sources were exaggerating, as they so often did, but it’s in keeping with Hephaestion’s importance to Alexander and the posthumous honors he received that the largest tomb ever found in Greece would have been built for him.

So according to Plutarch Alexander had decided against turning all of Mount Athos into a sort of pre-dynamite one-man Mount Rushmore monument to himself, but he planned to make an even more elaborate tomb for his beloved companion, one worthy of a divine hero. Perhaps Alexander’s death in 323 B.C. kept the crazier of the grandiose plans from taking hold or perhaps the ancient sources were exaggerating, as they so often did, but it’s in keeping with Hephaestion’s importance to Alexander and the posthumous honors he received that the largest tomb ever found in Greece would have been built for him.

According to the Greek Culture Ministry, the Kasta Tumulus has to have a public religious purpose like the tomb of a divine hero. The tomb used the greatest amount of marble ever assembled in Macedonia, and the variety and precision of decorative and architectural techniques — the sphinxes, painted architraves, pebble mosaics in the entryway, the Persephone tile mosaic, the caryatids, the lion that was once on top of the tomb — make it a uniquely complex project. Its size and scope was so massive no individual could have  mustered the resources to construct it. The archaeological team plans to examine the 430 or so marble elements from the tomb that the Romans stripped from the tomb in the 2nd century A.D. and used to shore up the banks of the river Strymon. Perhaps pieces from inside the tomb, fragments of the grave, for example, might be recovered that will lend additional insight.

mustered the resources to construct it. The archaeological team plans to examine the 430 or so marble elements from the tomb that the Romans stripped from the tomb in the 2nd century A.D. and used to shore up the banks of the river Strymon. Perhaps pieces from inside the tomb, fragments of the grave, for example, might be recovered that will lend additional insight.