As archaeologists dig deeper into the burial mound, ancient sources tell a tale of family drama and palace intrigue.

A mysterious royal tomb in Greece may hold a relative or associate of Alexander the Great, portrayed here in a mosaic from Pompeii.

Photograph by Araldo de Luca, Corbis

Published November 21, 2014

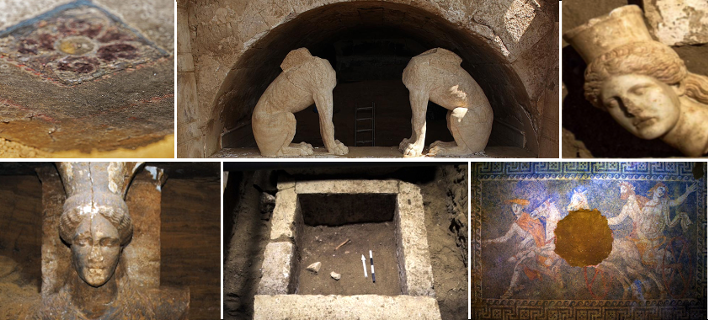

Suspense is rising as archaeologists sift for clues to the identity of the person buried with pomp and circumstance in the mysterious Amphipolis tomb in what is now northern Greece. The research team thinks the tomb was built for someone very close to Alexander the Great—his mother, Olympias; one of his wives, Roxane; one of his favorite generals; or possibly his childhood friend and lover, Hephaestion.

Over the past three months, archaeologist Katerina Peristeri and her team have made a series of tantalizing discoveries in the tomb, from columns sculpted masterfully in the shapes of young women to a mosaic floor depicting the abduction of the Greek goddess Persephone. The tomb’s costly artwork all dates to the tumultuous time around the death of Alexander the Great, and points to the presence of an important person.

Alexander himself was almost certainly buried in Egypt. But the final resting places—and the rich historical and genetic data they may contain—of many of his family members are unknown. The excavation at Amphipolis is bound to add a new chapter to the history of Alexander the Great and his family, a dynasty as steeped in intrigue, conspiracy, and bloodshed as the fictional Lannisters in the popular television series Game of Thrones. Among Alexander’s family, “the king or ruler who ended up dying in his bed was rare,” says Philip Freeman, a biographer of Alexander the Great and a classical historian at Luther College in Decorah, Iowa.

Palace Intrigues

To understand these palace intrigues, one must begin with Alexander’s father, Philip II, who ascended the throne of ancient Macedonia in 359 B.C. At the time, Macedonia was a modest mountain realm north of ancient Greece, but Philip had big dreams. He transformed Macedonia’s army from a band of ragtag fighters into a disciplined military machine, and he armed it with a deadly new weapon, the sarissa, a long lance designed to keep enemy troops from closing in on his phalanxes.

A natural-born conqueror, Philip led his army to the west, crushing and intimidating the major Greek city-states until all had surrendered to his rule. “Philip II was a traditional warrior king,” says Ian Worthington, author of By the Spear: Philip II, Alexander the Great, and the Rise and Fall of the Macedonian Empire. “He was always in the thick of battle.”

By custom, Macedonia’s kings married multiple wives, often for the purposes of sealing political alliances with powerful neighbors. Alexander’s mother, Olympias, was a daughter of the king of Molossia, a realm that encompassed part of modern Albania, and she claimed descent from the legendary Greek hero, Achilles. She was one of Philip’s many wives, and according to ancient historians, she schemed relentlessly at court to put her son on the Macedonian throne. Some historians even suspect that she poisoned Alexander’s older half-brother, impairing his mental faculties.

For a time, her intrigues seemed to succeed. Philip groomed the young Alexander as his heir, providing the boy with a first-class education from a renowned tutor, Aristotle, and encouraging his prowess as a warrior.

But important Macedonian nobles at Philip’s court viewed Alexander as half foreign and possibly illegitimate. By the time Alexander reached his late teens, Philip seemed to share these doubts. He took a new Macedonian wife, and during a drinking party, Philip allowed Alexander’s legitimacy to be publicly questioned. Then Philip drew his own sword on Alexander, a mortal insult.

Philip later tried to patch things up, but he had created a dangerous enemy. Exactly what happened next is the subject of debate, although the bare facts are well known. In 336 B.C., Philip threw a lavish public wedding for one of his daughters and invited members of neighboring royal houses to attend this state occasion.

As part of the festivities, Philip planned to stage public games at daybreak in the theater at Aigai, his capital city. He strode into the stadium, wearing a white cloak over his shoulders. On one side was Alexander; on the other was his new son-in-law. Philip waved away his bodyguards, and as he stood at the center of the theater, the large crowd began to roar with approval.

“That was the last thing he ever heard,” says Worthington. An assassin stepped out from the crowd and stabbed Philip to death as the guests watched in disbelief. In the ensuing bedlam, the murderer, a man named Pausanias, bolted from the theater toward a spot where horses were tethered and waiting for him. But just as Pausanias was about to escape, he tripped and fell, and three of Philip’s bodyguards speared him to death.

Conspiracy Theory

Did Pausanias act alone? Some ancient texts suggest that he did, assassinating Philip in a jealous rage. Many of the ancient Macedonian nobles were bisexual, and Philip was no exception. He had taken Pausanias as his lover, and when he tired of him, he discarded the young man and even allowed others to sexually abuse Pausanias. So Pausanias may have murdered Philip in an act of revenge.

But several clues point to a conspiracy, says Worthington. Pausanias, for example, fled to a spot where multiple horses were waiting, suggesting that several people had made plans for escaping the crime scene.

“I think Pausanias was manipulated to kill Philip,” says Worthington, who suspects that Olympias and Alexander played key parts in the assassination. Both mother and son had been deeply insulted by Philip. In addition, they may have feared that Philip’s young Macedonian wife would produce a Macedonian heir more acceptable to the local nobility. The only way to prevent this would be to eliminate Philip. So Worthington theorizes that Olympias and Alexander poisoned Pausanias’s mind and encouraged him to murder Philip.

Other classical historians aren’t so sure Alexander was guilty of patricide. Nevertheless, says Luther College’s Freeman, “if you put Alexander on a couch today and tried to analyze him, you could have a lot of fun.”

The King Is Dead, Long Live the King

With Philip gone, Alexander had to convince the Macedonian court that he deserved to be king. He planned a costly funeral for his father, cremating the body on a massive funeral pyre and constructing an elaborate tomb for Philip on the outskirts of Aigai (the modern Greek town of Vergina), some 100 miles from Amphipolis. As Macedonia’s aristocracy looked on, Alexander buried his father “like a Homeric hero,” says Ioannes Graekos, an archaeologist and curator at the Royal Tombs Museum in Vergina.

Inside the tomb, Alexander interred a gold chest containing Philip’s skeletal remains, as well as a host of royal treasures, from a gilded crown to a golden scepter, a gold cuirass, and a gold- and ivory-adorned deathbed. Over the doorway, the young king had artists paint a hunting scene showing Alexander and his father closing in on a lion.

“Only royalty can hunt lions, so Alexander was honoring his father, but he was also honoring himself,” says Terence Clark, an archaeologist at the Canadian Museum of History in Gatineau, Quebec, who, along with National Geographic and others, is helping to organize a major new traveling exhibition on the heroes of ancient Greece, including Alexander the Great. “It’s a definitive statement that Alexander is now in charge.”

But despite his appearance of confidence, Alexander still feared rivals at court. He ordered the deaths of his cousin Amyntas and of one of Philip’s young wards. And his mother, Olympias, took care of enemies among the royal women. According to at least one ancient text, she forced Philip’s young Macedonian wife to commit suicide and arranged for the murder of her rival’s daughter. Olympias, says Elizabeth Carney, a classical historian at Clemson University in South Carolina and biographer of Alexander’s mother, was “a political woman.”

That left just the army. Alexander had to convince Macedonia’s generals and soldiers alike that he was a commander like his father. So he embarked on a series of military campaigns, quelling rebels in the Balkan region, crushing the city-state of Thebes, and leading his army to one victory after another. By the time he turned 21, Alexander was firmly in control of Macedonia and Greece, and ready to embark on the conquest of Persia.

Alexander extended his rule to lands as far south as Egypt and as far east as India, creating one of the greatest empires of the ancient world. His closest companion was his lover Hephaestion, a Macedonian general, and when Hephaestion finally succumbed to a mysterious ailment in 324 B.C. on an eastern campaign, Alexander was nearly undone by grief. According to the ancient writer Plutarch, he had Hephaestion’s doctor crucified and massacred an entire tribe in the region to provide offerings for Hephaestion’s spirit.

Things Fall Apart

By the time of his own death at age 33, Alexander was still in the east, planning the conquest of Arabia. He clearly preferred the thrill of battle to the numbing minutiae of governing. He had taken at least two foreign wives, but had produced no legitimate heir to his massive empire and had given little apparent thought to the matter of succession. Soon after he died of a mysterious fever in Babylon, his generals, nobles, and family members began fighting bitterly over the succession. In the end, his vast empire was divided as spoils of a civil war, and his entire direct line was wiped out.

Alexander’s mother met her end at the hands of a ruthless Macedonian noble, Cassander. To clear the path to the Macedonian throne, Cassander took Olympias prisoner during a siege and executed her. Then, like Alexander himself, he set about eliminating other potential plotters. He imprisoned Alexander’s most important foreign wife, Roxane, and his posthumous son, Alexander IV, at Amphipolis—and had them both secretly murdered in 311 B.C. With the dirty work done, Cassander ruled the kingdom of Macedonia until his death in 297 B.C.

Most archaeologists today are convinced, based on historical accounts, that Alexander himself was buried somewhere in Egypt, quite possibly in the city that bears his name today, Alexandria. But researchers have yet to find the tombs of Olympias, Roxane, Hephaestion, and many of his generals. Perhaps the archaeological team clearing the mysterious tomb at Amphipolis will yet find the remains of one of them.