Geologist Evangelos Kambouroglou also said Saturday that the mound inside which the rooms and the tomb were found is not man-made, as archaeologists had assumed, but a natural hill.

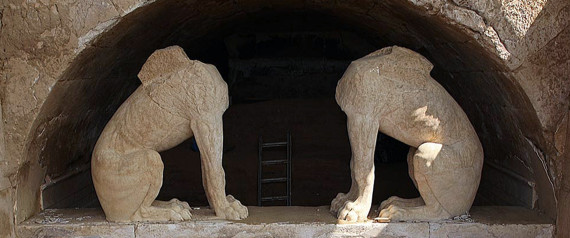

He also said that the Lion of Amphipolis, a huge sculpture of a lion on a pedestal , which is more than 25 feet (7.5 meters) tall, was too heavy to have stood at the top of the tomb, as archaeologists had claimed.

“The walls (of the tomb structure) can barely withstand half a ton, not 1,500 tons that the Lion sculpture is estimated to weigh,” Kambouroglou said.

As for the box-like tomb that contained the remnants of five bodies, possibly more, “it is posterior to the main burial monument … the main tomb has been destroyed by looters, who left nothing,” said Kambouroglou. “The marble doors (of the monument) contain signs of heavy use, which means many visitors came and went.”

The vaulted rooms had been dated to between 325 B.C. — two years before the death of ancient Greek warrior-king Alexander the Great — and 300 B.C., although some archaeologists had claimed a later date.

Katerina Peristeri, the chief archaeologist in the recent excavation, had advanced the theory that a member of Alexander's family, or one of his generals, could be buried in the tomb. But the discovery of the boxy grave and the five bodies cast doubt on that theory and Kambouroglou's announcement appears to disprove it entirely. Some archaeologists present during Saturday announcement criticized Peristeri's absence and her methods.

Alexander, who built an empire stretching from modern Greece to India, died in Babylon and was buried in the city of Alexandria, which he founded. The precise location of his tomb is one of the biggest mysteries of archaeology.

His generals fought over the empire for years, during wars in which Alexander's mother, widow, son and half-brother were all murdered — most near Amphipolis.

Costas Kantouris on twitter: @Costaskantouris

http://www.huffingtonpost.com