Hypatia’s life is most commonly seen through the lives of the two men in charge of Alexandria during her life: pagan governor Orestes and Bishop Cyril. It was in their life stories that Hypatia was written about, and it is only later literature that attempted to piece together her story outside of the politics of these two men. The evidence of her beginnings stem from two ancient sources: Socrates of Scholasticus, writing only a few years after she died, and John of Nikiu, writing a few hundred years later. Though these men write of Hypatia in relation to Orestes and Cyril, they provide the two most widely circulated theories of who she was during her lifetime, and thus serve as two of the best references.

Born around 350 CE, Hypatia was the daughter of a mathematician. She took an interest in science and math as well, eventually becoming the leading teacher of a Platonic school in Egypt, tutoring students in both astronomy and the philosophy of Plato and Plotis. It was because of her religious beliefs and the subjects she taught that she was later targeted by the Christians of Alexandria—a woman with such knowledge and intellectual skill was considered dangerous in this period. But her death was not solely because of her teachings. The current political struggle between the head of the church of Alexandria (Cyril) and the head of the government (Orestes) needed a scapegoat; since Hypatia was already making waves in society, she was the easiest and best target.

Hypatia teaching a class (Image source)

The conflict between Orestes and Cyril was a religious one. Orestes remained a pagan follower with what seemed to be a close, protective relationship with the Jewish community in the city, while Cyril, on the other hand, was a wholly Christian man. As the story goes, the two men were already feuding because of Cyril’s attempt to push ecclesiastical reforms throughout Alexandria. Their feud came to a head, however, when Orestes issued an edict dictating the rules of the Jewish dancing exhibitions, a particularly sore subject between the two men. A Christian under Cyril, Heirax, applauded the edict and was then accused by the Jews of having been sent to the hearing to anger and provoke them. To appease his subjects, Orestes had Heirax openly tortured and killed. But the Jews were indeed upset, and unfortunately for Orestes, took matters into their own hands.

In anger, the Jews of the city fooled the Christians into believing their church was ablaze in the middle of the night. According to both Socrates and John, when the Christians fled to the streets to save their beloved sanctuary, they were slaughtered. The result: the Jews were stripped of their worldly goods and banished by Cyril, and Orestes was attacked—supposedly by five hundred monks. It was only after one of these monks, Ammonius, was declared a martyr upon his death that the Christians themselves realized the terrible irony of his martyrdom title. It was at this moment that Hypatia’s life was stolen and rewritten to play the part of scapegoat.

According to John of Nikiu, Hypatia was not merely a philosopher and scholar. She was a woman of magical wiles who practiced ‘Satanic charms’ and had enchanted the governor Orestes. It seemed that Orestes was known to bring Hypatia into his confidence often, evidenced by numerous ancient and medieval scholars, and because of this the Christians and John of Nikiu seemed to believe that she was behind all the actions and decisions of Orestes. John of Nikiu claims, in a sense, that she charmed Orestes to do her bidding.

Illustration from an 1899 edition of Charles Kingsley’s 1853 novel Hypatia. Picture shows Hypatia performing a pagan ritual (Wikimedia).

Both Socrates Scholasticus and John of Nikiu—and nearly every other text that describes Hypatia’s life—tell the same story of her end, of the actions the Christians took to silence her “power” over Orestes. Hypatia was hunted down and kidnapped by a magistrate called Peter and his fellow Christians and taken to the church at Caesareum. Brutally, she was stripped of her clothes and beaten with tiles or oyster shells, supposedly skinned alive with those very same oyster shells. Then, Hypatia was either ripped to shreds or dragged through the streets until she died. Regardless of the specifics, both men describe a murder so brutal, so callous, Hypatia was definitely treated more like an animal up for the slaughter than a human being accused of wronging the government. Whether or not she had worked closely with Orestes, the way of her death was horrific and undeserved.

“Death of the philosopher Hypatia, in Alexandria” from the book Vies des savants illustres, depuis l’antiquité jusqu’au dix-neuvième siècle, by Louis Figuier, first published 1866. [Note: this picture has a racist overtone and should not be seen as an accurate representation of Hypatia’s killers. However, it does reflect the historical descriptions of Hypatia being dragged through the street]. (Wikimedia)

Despite this, the majority of Hypatia’s life has been written about in relation to how her death impacted on the city of Alexandria in the 4th century, not about the injustice of her murder. While she was alive, she was known as a great female philosophical leader. But in history, she is best remembered for the role she was accused of playing in the political struggle between two overconfident, religiously warring men. With her death, many scholars believe the cultural scales in Alexandria tipped: John of Nikiu proclaimed that the final threads of pagan idolatry ended with her, while modern scholars believe that classical and Alexandrian culture completely deteriorated. Regardless of whether this belief is true, whether Hypatia can truly be identified as the end of the height of Alexandrian society, her death did create a political and religious shift throughout Alexandria and the eastern Roman Empire.

Featured image: ‘Hypatia’ by Alfred Seifert, 1901 (Wikimedia).

Sources:

Dzielska, Maria. Hypatia of Alexandria. trans. F. Lyra. (Harvard University Press: Connecticut, 1996.)

Charles, R. H., The Chronicle of John, Bishop of Nikiu: Translated from Zotenberg’s Ethiopic Text (New Jersey: Evolution Publishing, 2007.)

FitzGerald, A., The Letters of Synesius of Cyrene (London: Oxford University Press, 1926.)

Schaefer, Francis. “St. Cyril of Alexandria and the Murder of Hypatia”, The Catholic University Bulletin 8, 1992. pp. 441–453.

Scholasticus, Socrates. Historia Ecclesiastica (NuVision Publications, LLC: South Dakota, 2013.)

Whitfield, Bryan J. “The Beauty of Reasoning: A Reexamination of Hypatia and Alexandria”. The Mathematics Educator, 1995. pp. 14–21. Accessed November 2, 2014.

Zielinski, Sarah. “Hypatia, Ancient Alexandria’s Great Female Scholar.” Smithsonian Magazine. March 14, 2010. Accessed November 2, 2014. http://www.smithsonianmag.com/womens-history/hypatia-ancient-alexandrias-great-female-scholar-10942888/?page=1.

Greece is a country where we are constantly reminded of its ancient history while engaging in modern pursuits. A car speeds through the streets of Athens with the Parthenon in the backdrop. A tourist gazes at the ocean view from the Temple of Poseidon while snapping a picture with his cell phone. Wine is one example of when modern life intersects with ancient tradition because it represents the past, present, and future of the Greek people.

Greece is a country where we are constantly reminded of its ancient history while engaging in modern pursuits. A car speeds through the streets of Athens with the Parthenon in the backdrop. A tourist gazes at the ocean view from the Temple of Poseidon while snapping a picture with his cell phone. Wine is one example of when modern life intersects with ancient tradition because it represents the past, present, and future of the Greek people. MISIS, TURKEY—An enduring history is being revealed in southern Turkey at the ancient site of Misis, reports

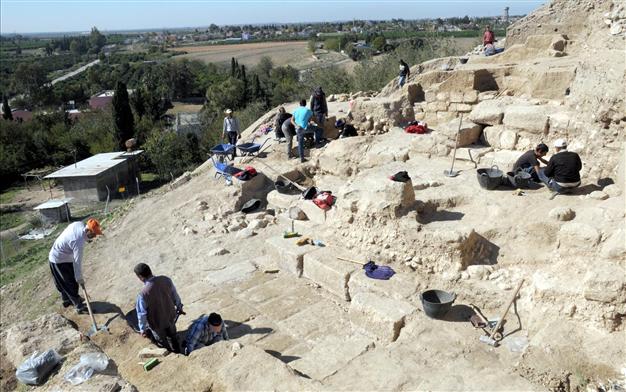

MISIS, TURKEY—An enduring history is being revealed in southern Turkey at the ancient site of Misis, reports