Κατηγορία: english

Amphipolis.gr | Greco-Buddhist art

Greco-Buddhist art is the artistic manifestation of Greco-Buddhism, a cultural syncretism between the Classical Greek culture and Buddhism, which developed over a period of close to 1000 years in Central Asia, between the conquests of Alexander the Great in the 4th century BC, and the Islamic conquests of the 7th century AD. Greco-Buddhist art is characterized by the strong idealistic realism and sensuous description of Hellenistic art and the first representations of the Buddha in human form, which have helped define the artistic (and particularly, sculptural) canon for Buddhist art throughout the Asian continent up to the present. It is also a strong example of cultural syncretism between eastern and western traditions.

The origins of Greco-Buddhist art are to be found in the Hellenistic Greco-Bactrian kingdom (250 BC- 130 BC), located in today’s Afghanistan, from which Hellenistic culture radiated into the Indian subcontinent with the establishment of the Indo-Greek kingdom (180 BC-10 BC). Under the Indo-Greeks and then the Kushans, the interaction of Greek and Buddhist culture flourished in the area of Gandhara, in today’s northern Pakistan, before spreading further into India, influencing the art of Mathura, and then the Hindu art of the Gupta empire, which was to extend to the rest of South-East Asia. The influence of Greco-Buddhist art also spread northward towards Central Asia, strongly affecting the art of the Tarim Basin, and ultimately the arts of China, Korea, and Japan.

Hellenistic art in southern Asia

Powerful Hellenistic states were established in the areas of Bactria and Sogdiana, and later northern India for three centuries following the conquests of Alexander the Great around 330 BC, the Seleucid empire until 250 BC, followed by the Greco-Bactrian kingdom until 130 BC, and the Indo-Greek kingdom from 180 BC to around 10 BC.

The clearest examples of Hellenistic art are found in the coins of the Greco-Bactrian kings of the period, such as Demetrius I of Bactria. Many coins of the Greco-Bactrian kings have been unearthed, including the largest silver and gold coins ever minted in the Hellenistic world, ranking among the best in artistic and technical sophistication: they “show a degree of individuality never matched by the often more bland descriptions of their royal contemporaries further West”. (“Greece and the Hellenistic world”).

These Hellenistic kingdoms established cities on the Greek model, such as in Ai-Khanoum in Bactria, displaying purely Hellenistic architectural features, Hellenistic statuary, and remains of Aristotelician papyrus prints and coin hoards.

These Greek elements penetrated in northwestern India following the invasion of the Greco-Bactrians in 180 BC, when they established the Indo-Greek kingdom in India. Fortified Greek cities, such as Sirkap in northern Pakistan, were established. Architectural styles used Hellenistic decorative motifs such as fruit garland and scrolls. Stone palettes for aromatic oils representing purely Hellenistic themes such as a Nereid riding a Ketos sea monster are found.

In Hadda, Hellenistic deities, such as Atlas are found. Wind gods are depicted, which will affect the representation of wind deities as far as Japan. Dionysiac scenes represent people in Classical style drinking wine from amphoras and playing instruments.

Interaction

As soon as the Greeks invaded India to form the Indo-Greek kingdom, a fusion of Hellenistic and Buddhist elements started to appear, encouraged by the benevolence of the Greek kings towards Buddhism. This artistic trend then developed for several centuries and seemed to flourish further during the Kushan Empire from the 1st century AD.

Artistic model

Greco-Buddhist art depicts the life of the Buddha in a visual manner, probably by incorporating the real-life models and concepts which were available to the artists of the period.

The Bodhisattvas are depicted as bare-chested and jewelled Indian princes, and the Buddhas as Greek kings wearing the light toga-like himation. The buildings in which they are depicted incorporate Greek style, with the ubiquitous Indo-Corinthian capitals and Greek decorative scrolls. Surrounding deities form a pantheon of Greek (Atlas, Herakles) and Indian gods (Indra).

Material

Stucco as well as stone was widely used by sculptors in Gandhara for the decoration of monastic and cult buildings. Stucco provided the artist with a medium of great plasticity, enabling a high degree of expressiveness to be given to the sculpture. Sculpting in stucco was popular wherever Buddhism spread from Gandhara – India, Afghanistan, Central Asia and China.

Stylistic evolution

Stylistically, Greco-Buddhist art started by being extremely fine and realistic, as apparent on the standing Buddhas, with “a realistic treatment of the folds and on some even a hint of modelled volume that characterizes the best Greek work” (Boardman). It then lost this sophisticated realism, becoming progressively more symbolic and decorative over the centuries.

Architecture

The presence of stupas at the Greek city of Sirkap, which was built by Demetrius around 180 BC, already indicates a strong syncretism between Hellenism and the Buddhist faith, together with other religions such as Hinduism and Zoroastrianism. The style is Greek, adorned with Corinthian columns in excellent Hellenistic execution.

Later in Hadda, the Greek divinity Atlas is represented holding Buddhist monuments with decorated Greek columns. The motif was adopted extensively throughout the Indian sub-continent, Atlas being substituted for the Indian Yaksa in the monuments of the Sunga around the 2nd century BC.

Buddha

Sometime between the 2nd century BC and the 1st century AD, the first anthropomorphic representations of the Buddha were developed. These were absent from earlier strata of Buddhist art, which preferred to represent the Buddha with symbols such as the stupa, the Bodhi tree, the empty seat, the wheel, or the footprints. But the innovative anthropomorphic Buddha image immediately reached a very high level of sculptural sophistication, naturally inspired by the sculptural styles of Hellenistic Greece.

Many of the stylistic elements in the representations of the Buddha point to Greek influence: the Greek himation (a light toga-like wavy robe covering both shoulders: Buddhist characters are always represented with a dhoti loincloth before this innovation), the halo, the contrapposto stance of the upright figures, the stylized Mediterranean curly hair and top-knot apparently derived from the style of the Belvedere Apollo (330 BC), and the measured quality of the faces, all rendered with strong artistic realism (See: Greek art). Some of the standing Buddhas (as the one pictured) were sculpted using the specific Greek technique of making the hands and sometimes the feet in marble to increase the realistic effect, and the rest of the body in another material.

Foucher especially considered Hellenistic free-standing Buddhas as “the most beautiful, and probably the most ancient of the Buddhas”, assigning them to the 1st century BC, and making them the starting point of the anthropomorphic representations of the Buddha (“The Buddhist art of Gandhara”, Marshall, p101).

Development

There is some debate regarding the exact date for the development of the anthropomorphic representation of the Buddha, and this has a bearing on whether the innovation came directly from the Indo-Greeks, or was a later development by the Indo-Scythians, the Indo-Parthians or the Kushans under Hellenistic artistic influence. Most of the early images of the Buddha (especially those of the standing Buddha) are anepigraphic, which makes it difficult to have a definite dating. The earliest known image of the Buddha with approximate indications on date is the Bimaran casket, which has been found buried with coins of the Indo-Scythian king Azes II (or possibly Azes I), indicating a 30-10 BC date, although this date is not undisputed.

Such datation, as well as the general Hellenistic style and attitude of the Buddha on the Bimaran casket (himation dress, contrapposto attitude, general depiction) would made it a possible Indo-Greek work, used in dedications by Indo-Scythians soon after the end of Indo-Greek rule in the area of Gandhara. Since it already displays quite a sophisticated iconography (Brahma and Śakra as attendants, Bodhisattvas) in an advanced style, it would suggest much earlier representations of the Buddha were already current by that time, going back to the rule of the Indo-Greeks (Alfred A. Foucher and others).

The next Greco-Buddhist findings to be strictly datable are rather late, such as the c.AD 120 Kanishka casket and Kanishka‘s Buddhist coins. These works at least indicate though that the anthropomorphic representation of the Buddha was already extant in the 1st century AD.

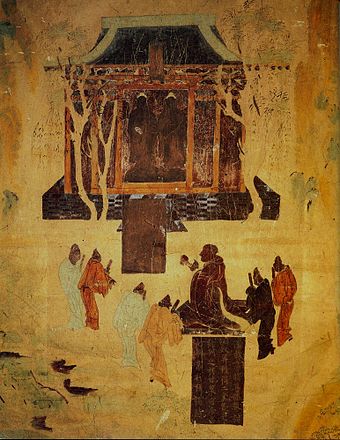

From another direction, Chinese historical sources and mural paintings in the Tarim Basin city of Dunhuang accurately describe the travels of the explorer and ambassador Zhang Qian to Central Asia as far as Bactria around 130 BC, and the same murals describe the Emperor Han Wudi (156-87 BC) worshipping Buddhist statues, explaining them as “golden men brought in 120 BC by a great Han general in his campaigns against the nomads.” Although there is no other mention of Han Wudi worshipping the Buddha in Chinese historical literature, the murals would suggest that statues of the Buddha were already in existence during the 2nd century BC, connecting them directly to the time of the Indo-Greeks.

Later, the Chinese historical chronicle Hou Hanshu describes the enquiry about Buddhism made around AD 67 by the emperor Emperor Ming (AD 58-75). He sent an envoy to the Yuezhi in northwestern India, who brought back paintings and statues of the Buddha, confirming their existence before that date:

- “The Emperor, to discover the true doctrine, sent an envoy to Tianzhu (天竺, Northwestern India) (Northwestern India) to inquire about the Buddha’s doctrine, after which paintings and statues [of the Buddha] appeared in the Middle Kingdom.” (Hou Hanshu, trans. John Hill)

An Indo-Chinese tradition also explains that Nagasena, also known as Menander‘s Buddhist teacher, created in 43 BC in the city of Pataliputra a statue of the Buddha, the Emerald Buddha, which was later brought to Thailand.

In Gandharan art, the Buddha is often shown under the protection of the Greek god Herakles, standing with his club (and later a diamond rod) resting over his arm.[1] This unusual representation of Herakles is the same as the one on the back of Demetrius’ coins, and it is exclusively associated to him (and his son Euthydemus II), seen only on the back of his coins.

Soon, the figure of the Buddha was incorporated within architectural designs, such as Corinthian pillars and friezes. Scenes of the life of the Buddha are typically depicted in a Greek architectural environment, with protagonist wearing Greek clothes.

Gods and Bodhisattvas

Deities from the Greek mythological pantheon also tend to be incorporated in Buddhist representations, displaying a strong syncretism. In particular, Herakles (of the type of the Demetrius coins, with club resting on the arm) has been used abundantly as the representation of Vajrapani, the protector of the Buddha.[2] Other Greek deities abundantly used in Greco-Buddhist art are representation of Atlas, and the Greek wind god Boreas. Atlas in particular tends to be involved as a sustaining elements in Buddhist architectural elements. Boreas became the Japanese wind god Fujin through the Greco-Buddhist Wardo. The mother deity Hariti was inspired by Tyche.

Particularly under the Kushans, there are also numerous representations of richly adorned, princely Bodhisattvas all in a very realistic Greco-Buddhist style. The Bodhisattvas, characteristic of the Mahayana form of Buddhism, are represented under the traits of Kushan princes, completed with their canonical accessories.

Cupids

Winged cupids are another popular motif in Greco-Buddhist art. They usually fly in pair, holding a wreath, the Greek symbol of victory and kingship, over the Buddha.

These figures, also known as “apsarases” were extensively adopted in Buddhist art, especially throughout Eastern Asia, in forms derivative to the Greco-Buddhist representation. The progressive evolution of the style can be seen in the art of Qizil and Dunhuang. It is unclear however if the concept of the flying cupids was brought to India from the West, of if it had an independent Indian origin, although Boardman considers it a Classical contribution: “Another Classical motif we found in India is the pair of hovering winged figures, generally called apsaras.” (Boardman)

Scenes of cupids holding rich garlands, sometimes adorned with fruits, is another very popular Gandharan motif, directly inspired from Greek art. It is sometimes argued that the only concession to Indian art appears in the anklets worn by the cupids. These scenes had a very broad influence, as far as Amaravati on the eastern coast of India, where the cupids are replaced by yakṣas.

Devotees

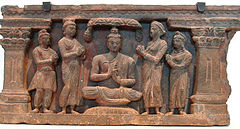

Some Greco-Buddhist friezes represent groups of donors or devotees, giving interesting insights into the cultural identity of those who participated in the Buddhist cult.

Some groups, often described as the “Buner reliefs,” usually dated to the 1st century AD, depict Greeks in perfect Hellenistic style, either in posture, rendering, or clothing (wearing the Greek chiton and himation). It is sometimes even difficult to perceive an actual religious message behind the scenes. (The devotee scene on the right might, with doubt, depict of the presentation of Prince Siddharta to his bride. It may also just be a festive scene.)

About a century later, friezes also depict Kushan devotees, usually with the Buddha as the central figure.

Fantastic animals

Various fantastic animal deities of Hellenic origin were used as decorative elements in Buddhist temples, often triangular friezes in staircases or in front of Buddhist altars. The origin of these motifs can be found in Greece in the 5th century BC, and later in the designs of Greco-Bactrian perfume trays as those discovered in Sirkap. Among the most popular fantastic animals are tritons, ichthyo-centaurs and ketos sea-monsters. It should be noted that similar fantastic animals are found in ancient Egyptian reliefs, and might therefore have been passed on to Bactria and India independently of Greek imperialism.

As fantastic animals of the sea, they were, in early Buddhism, supposed to safely bring the souls of dead people to Paradise beyond the waters. These motifs were later adopted in Indian art, where they influenced the depiction of the Indian monster makara, Varuna‘s mount.

Kushan contribution

The later part of Greco-Buddhist art in northwestern India is usually associated with the Kushan Empire. The Kushans were nomadic people who started migrating from the Tarim Basin in Central Asia from around 170 BC and ended up founding an empire in northwestern India from the 2nd century BC, after having been rather Hellenized through their contacts with the Greco-Bactrians, and later the Indo-Greeks (they adopted the Greek script for writing).

The Kushans, at the centre of the Silk Road enthusiastically gathered works of art from all the quarters of the ancient world, as suggested by the hoards found in their northern capital in the archeological site of Begram, Afghanistan.

The Kushans sponsored Buddhism together with other Iranian and Hindu faiths, and probably contributed to the flourishing of Greco-Buddhist art. Their coins, however, suggest a lack of artistic sophistication: the representations of their kings, such as Kanishka, tend to be crude (lack of proportion, rough drawing), and the image of the Buddha is an assemblage of a Hellenistic Buddha statue with feet grossly represented and spread apart in the same fashion as the Kushan king. This tends to indicate the anteriority of the Hellenistic Greco-Buddhist statues, used as models, and a subsequent corruption by Kushan artists.

Southern influences

Art of the Sunga

Examples of the influence of Hellenistic or Greco-Buddhist art on the art of the Sunga empire (183-73 BC) are usually faint. The main religion, at least at the beginning, seems to have been Brahmanic Hinduism, although some late Buddhist realizations in Madhya Pradesh as also known, such as some architectural expansions that were done at the stupas of Sanchi and Bharhut, originally started under King Ashoka.

This Sunga-period balustrate-holding Atalante[disambiguation needed] Yaksa from the Sunga period (left), adopts the Atalante[disambiguation needed] theme, usually fulfilled by Atlas, and elements of Corinthian capital and architecture typical of Greco-Buddhist friezes from the Northwest, although the content does not seem to be related to Buddhism. This work suggests that some of the Gandharan friezes, influential to this work, may have existed as early as the 2nd century or 1st century BC.

Other Sunga works show the influence of floral scroll patterns, and Hellenistic elements in the rendering of the fold of dresses. The 2nd century BC depiction of an armed foreigner (right), probably a Greek king, with Buddhist symbolism (triratana symbol of the sword), also indicates some kind of cultural, religious, and artistic exchange at that point of time.

Art of Mathura

The representations of the Buddha in Mathura, in central northern India, are generally dated slightly later than those of Gandhara, although not without debate, and are also much less numerous. Up to that point, Indian Buddhist art had essentially been aniconic, avoiding representation of the Buddha, except for his symbols, such as the wheel or the Bodhi tree, although some archaic Mathuran sculptural representation of Yaksas (earth divinities) have been dated to the 1st century BC. Even these Yaksas indicate some Hellenistic influence, possibly dating back to the occupation of Mathura by the Indo-Greeks during the 2nd century BC.

In terms of artistic predispositions for the first representations of the Buddha, Greek art provided a very natural and centuries-old background for an anthropomorphic representation of a divinity, whether on the contrary “there was nothing in earlier Indian statuary to suggest such a treatment of form or dress, and the Hindu pantheon provided no adequate model for an aristocratic and wholly human deity” (Boardman).

The Mathura sculptures incorporate many Hellenistic elements, such as the general idealistic realism, and key design elements such as the curly hair, and folded garment. Specific Mathuran adaptations tend to reflect warmer climatic conditions, as they consist in a higher fluidity of the clothing, which progressively tend to cover only one shoulder instead of both. Also, facial types also tend to become more Indianized. Banerjee in “Hellenism in India” describes “the mixed character of the Mathura School in which we find on the one hand, a direct continuation of the old Indian art of Bharut and Sanchi and on the other hand, the classical influence derived from Gandhara”.

The influence of Greek art can be felt beyond Mathura, as far as Amaravati on the East coast of India, as shown by the usage of Greek scrolls in combination with Indian deities. Other motifs such as Greek chariots pulled by four horses can also be found in the same area.

Incidentally, Hindu art started to develop from the 1st to the 2nd century AD and found its first inspiration in the Buddhist art of Mathura. It progressively incorporated a profusion of original Hindu stylistic and symbolic elements however, in contrast with the general balance and simplicity of Buddhist art.

The art of Mathura features frequent sexual imagery. Female images with bare breasts, nude below the waist, displaying labia and female genitalia are common. These images are more sexually explicit than those of earlier or later periods.

Art of the Gupta

The art of Mathura acquired progressively more Indian elements and reached a very high sophistication during the Gupta Empire, between the 4th and the 6th century AD. The art of the Gupta is considered as the pinnacle of Indian Buddhist art.

Hellenistic elements are still clearly visible in the purity of the statuary and the folds of the clothing, but are improved upon with a very delicate rendering of the draping and a sort of radiance reinforced by the usage of pink sandstone.

Artistic details tend to be less realistic, as seen in the symbolic shell-like curls used to render the hairstyle of the Buddha.

Expansion in Central Asia

Greco-Buddhist artistic influences naturally followed Buddhism in its expansion to Central and Eastern Asia from the 1st century BC.

Bactria

Bactria was under direct Greek control for more than two centuries from the conquests of Alexander the Great in 332 BC to the end of the Greco-Bactrian kingdom around 125 BC. The art of Bactria was almost perfectly Hellenistic as shown by the archaeological remains of Greco-Bactrian cities such as Alexandria on the Oxus (Ai-Khanoum), or the numismatic art of the Greco-Bactrian kings, often considered as the best of the Hellenistic world, and including the largest silver and gold coins ever minted by the Greeks.

When Buddhism expanded in Central Asia from the 1st century AD, Bactria saw the results of the Greco-Buddhist syncretism arrive on its territory from India, and a new blend of sculptural representation remained until the Islamic invasions.

The most striking of these realizations are the Buddhas of Bamyan. They tend to vary between the 5th and the 9th century AD. Their style is strongly inspired by Hellenistic culture.

In another area of Bactria called Fondukistan, some Greco-Buddhist art survived until the 7th century in Buddhist monasteries, displaying a strong Hellenistic influence combined with Indian decorativeness and mannerism, and some influence by the Sasanid Persians.

Most of the remaining art of Bactria was destroyed from the 5th century onward: the Buddhists were often blamed for idolatry and tended to be persecuted by the iconoclastic Muslims. Destructions continued during the Afghanistan War, and especially by the Taliban regime in 2001. The most famous case is that of the destruction of the Buddhas of Bamyan. Ironically, most of the remaining art from Afghanistan still extant was removed from the country during the Colonial period. In particular, a rich collection exists at the Musee Guimet in France.

Tarim Basin

The art of the Tarim Basin, also called Serindian art, is the art that developed from the 2nd through the 11th century AD in Serindia or Xinjiang, the western region of China that forms part of Central Asia. It derives from the art of the Gandhara and clearly combines Indian traditions with Greek and Roman influences.

Buddhist missionaries travelling on the Silk Road introduced this art, along with Buddhism itself, into Serindia, where it mixed with Chinese and Persian influences.

Influences in Eastern Asia

The arts of China, Korea and Japan adopted Greco-Buddhist artistic influences, but tended to add many local elements as well. What remains most readily identifiable from Greco-Buddhist art are:

- The general idealistic realism of the figures reminiscent of Greek art.

- Clothing elements with elaborate Greek-style folds.

- The curly hairstyle characteristic of the Mediterranean.

- In some Buddhist representations, hovering winged figures holding a wreath.

- Greek sculptural elements such as vines and floral scrolls.

China

Greco-Buddhist artistic elements can be traced in Chinese Buddhist art, with several local and temporal variations depending on the character of the various dynasties that adopted the Buddhist faith. Some of the earliest known Buddhist artifacts found in China are small statues on “money trees”, dated circa AD 200, in typical Gandharan style (drawing): “That the imported images accompanying the newly arrived doctrine came from Gandhara is strongly suggested by such early Gandhara characteristics on this “money tree” Buddha as the high ushnisha, vertical arrangement of the hair, moustache, symmetrically looped robe and parallel incisions for the folds of the arms.” “Crossroads of Asia” p209

Some Northern Wei statues can be quite reminiscent of Gandharan standing Buddha, although in a slightly more symbolic style. The general attitude and rendering of the dress however remain. Other, like Northern Qi Dynasty statues also maintain the general Greco-Buddhist style, but with less realism and stronger symbolic elements.

Some Eastern Wei statues display Buddhas with elaborate Greek-style robe foldings, and surmounted by flying figures holding a wreath.

Japan

In Japan, Buddhist art started to develop as the country converted to Buddhism in AD 548. Some tiles from the Asuka period, the first period following the conversion of the country to Buddhism, display a strikingly classical style, with ample Hellenistic dress and realistically rendered body shape characteristic of Greco-Buddhist art.

Other works of art incorporated a variety of Chinese and Korean influences, so that Japanese Buddhist became extremely varied in its expression. Many elements of Greco-Buddhist art remain to this day however, such as the Hercules inspiration behind the Nio guardian deities in front of Japanese Buddhist temples, or representations of the Buddha reminiscent of Greek art such as the Buddha in Kamakura.[3]

Left: Greek wind god from Hadda, 2nd century.

Middle: wind god from Kizil, Tarim Basin, 7th century.

Right: Japanese wind god Fujin, 17th century.

Various other Greco-Buddhist artistic influences can be found in the Japanese Buddhist pantheon, the most striking of which being that of the Japanese wind god Fujin. In consistency with Greek iconography for the wind god Boreas, the Japanese wind god holds above his head with his two hands a draping or “wind bag” in the same general attitude.[4] The abundance of hair have been kept in the Japanese rendering, as well as exaggerated facial features.

1) Herakles (Louvre Museum).

2) Herakles on coin of Greco-Bactrian king Demetrius I.

3) Vajrapani, the protector of the Buddha, depicted as Herakles in the Greco-Buddhist art of Gandhara.

4) Shukongōshin, manifestation of Vajrapani, as protector deity of Buddhist temples in Japan.

Another Buddhist deity, named Shukongoshin, one of the wrath-filled protector deities of Buddhist temples in Japan, is also an interesting case of transmission of the image of the famous Greek god Herakles to the Far-East along the Silk Road. Herakles was used in Greco-Buddhist art to represent Vajrapani, the protector of the Buddha, and his representation was then used in China and Japan to depict the protector gods of Buddhist temples.[5]

Finally, the artistic inspiration from Greek floral scrolls is found quite literally in the decoration of Japanese roof tiles, one of the only remaining elements of wooden architecture to have survived the centuries. The clearest ones are from 7th century Nara temple building tiles, some of them exactly depicting vines and grapes. These motifs have evolved towards more symbolic representations, but essentially remain to this day in many Japanese traditional buildings.[6]

Influences on South-East Asian art

The Indian civilization proved very influential on the cultures of South-East Asia. Most countries adopted Indian writing and culture, together with Hinduism and Mahayana and Theravada Buddhism.

The influence of Greco-Buddhist art is still visible in most of the representation of the Buddha in South-East Asia, through their idealism, realism and details of dress, although they tend to intermix with Indian Hindu art, and they progressively acquire more local elements.

Cultural significance

Beyond stylistic elements which spread throughout Asia for close to a millennium, the main contribution of Greco-Buddhist art to the Buddhist faith may be in the Greek-inspired idealistic realism which helped describe in a visual and immediately understandable manner the state of personal bliss and enlightenment proposed by Buddhism. The communication of deeply human approach of the Buddhist faith, and its accessibility to all have probably benefited from the Greco-Buddhist artistic syncretism.

Museums

Major collections

- Peshawar Museum, Peshawar, Pakistan (largest collection in the world).

- Lahore Museum, Lahore, Pakistan.

- Taxila Museum, Taxila, Pakistan.

- National Museum of Pakistan, Karachi, Pakistan.

- Indian Museum, Kolkata, West Bengal, India.

- Mathura Museum, Mathura, India.

- Musée Guimet, Paris, France (about 150 artifacts, largest collection outside of Asia.)

- British Museum, London, Great Britain (about 100 artifacts), such as Seated Buddha from Gandhara

- Tokyo National Museum, Tokyo, Japan (about 50 artifacts)

- National Museum of Oriental Art, Rome, Italy (about 80 artifacts)

- Museum of Indian Art, Dahlem, Berlin, Germany.

Small collections

- Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA

- Ancient Orient Museum, Tokyo, Japan (About 20 artifacts)

- Victoria and Albert Museum, London, Great Britain (About 30 artifacts)

- City Museum of Ancient Art in Palazzo Madama, Turin, Italy.

- Rubin Museum of Art in New York City, NY, United States.

- National Museum, New Delhi, India

Private collections

Defining beauty: the Body in Ancient Greek Art at the British Museum gives visitors quite an eyeful

Amphipolis.gr | The precious remains of Akrotiri, an ancient city obliterated in the great eruption of Thera

The destruction of Pompeii by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in A.D. 79 has been preserved in ancient times by an eye witness account, namely that of Pliny the Younger. The literary evidence and amazing finds from the site has made Pompeii one of the most well-known archaeological sites in the world. It should be noted that Pompeii (and Herculaneum) are not entirely unique, as at least one other site it the ancient world has been destroyed by a volcanic eruption. The settlement of Akrotiri is one such site. Unlike Pompeii, however, no literary evidence for the destruction of Akrotiri is available to us. As a matter of fact, the city was only discovered by an archaeological excavation conducted in 1967.

The archaeological site of Akrotiri. Source: BigStockPhoto

Akrotiri was a Bronze Age settlement located on the south west of the island of Santorini (Thera) in the Greek Cyclades. This settlement is believed to be associated with the Minoan civilization, located on the nearby island of Crete, due to the discovery of the inscriptions in Linear A script, as well as similarities in artifacts and fresco styles. The earliest evidence for human habitation of Akrotiri can be traced back as early as the 5th millennium B.C., when it was a small fishing and farming village. By the end of the 3rd millennia, this community developed and expanded significantly. One factor for Akrotiri’s growth may be the trade relations it established with other cultures in the Aegean, as evidenced in fragments of foreign pottery at the site. Akrotiri’s strategic position between Cyprus and Minoan Crete also meant that it was situated on the copper trade route, thus allowing them to become an important center for processing copper, as proven by the discovery of molds and crucibles there.

Remarkably preserved artifacts are revealed from the ruins of ancient Akrotiri, Greece. Source: BigStockPhoto

Akrotiri’s prosperity continued for about another 500 years. Paved streets, an extensive drainage system, the production of high quality pottery, and further craft specialization all point to the level of sophistication achieved by the settlement. This all came to an end, however, by the middle of the 2nd century B.C. with the volcanic eruption of Thera. Although the powerful eruption destroyed Akrotiri, it also managed to preserve the city, very much like that done by Vesuvius to Pompeii.

The volcanic ash has preserved much of Akrotiri’s frescoes, which can be found in the interior walls of almost all the houses that have been excavated in Akrotiri. This may be an indication that it was not only the elites who had these works of art. The frescoes contain a wide range of subjects, including religious processions, flowers, everyday life in Akrotiri, and exotic animals. In addition, the volcanic dust also preserved negatives of disintegrated wooden objects, such as offering tables, beds, and chairs. This allowed archaeologists to produce plaster casts of these objects by pouring liquid Plaster of Paris into the hollows left behind by the objects. One striking difference between Akrotiri and Pompeii is that there were no uninterred bodies from in the former. In other words, the inhabitants of Akrotiri were perhaps more fortunate than those of Pompeii, and were evacuated before the volcanic dust reached the site.

Plaster castings of the corpses of a group of human victims of the 79 AD eruption of the Vesuvius, found in the so-called “Garden of the fugitives” in Pompeii. No such remains exist at Akrotiri, indicating the people had time to evacuate. Wikimedia, CC

‘Spring flowers and swallows’ detailed in a delicate Akrotiri fresco. Public Domain

The eruption of Thera also had an impact on other civilizations. The nearby Minoan civilization, for instance, faced a crisis due to the volcanic eruption. This is debatable, however, as some have speculated that the crisis was caused by natural disasters occurring prior to the eruption of Thera. The short term climate change caused by the volcanic eruption is also believed to have disrupted the ancient Egyptian civilization. The lack of Egyptian records regarding the eruption may be attributed to the general disorder in Egypt during the Second Intermediate Period. Nevertheless, the available records speak of heavy rainstorms occurring in the land, which is an unusual phenomenon. These storms may also be interpreted metaphorically as representing the elements of chaos that needed to be subdued by the Pharaoh. Some researchers have even claimed that the effects of the volcanic eruption were felt as far away as China. This is based on records detailing the collapse of the Xia Dynasty at the end of the 17th century B.C., and the accompanying meteorological phenomena. Finally, the Greek myth of the Titanomachy in Hesiod’s Theogony may have been inspired by this volcanic eruption, whilst it has also been speculated that Akrotiri was the basis of Plato’s myth of Atlantis. Thus, Akrotiri and the eruption of Thera serve to show that even in ancient times, a catastrophe in one part of the world can have repercussions on a global scale, something that we are more used to in the better connected world of today.

Featured image: Elaborate and colorful fresco revealed at Akrotiri. Public Domain

References

Cartwright, M., 2012. Thera. [Online] Available at: http://www.ancient.eu/thera/

de Traci, R., 2014. Akrotiri, Santorini’s Mystery. [Online] Available at: http://gogreece.about.com/library/weekly/aa08119b.htm

www.perseus.tufts.edu, 2014. Akrotiri, Thera (Site). [Online] Available at: http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/artifact?name=Akrotiri,+Thera&object=site

www.sacred-destinations.com, 2014. Ancient Akrotiri, Santorini. [Online] Available at: http://www.sacred-destinations.com/greece/santorini-akrotiri

www.santorini.com, 2014. Archaeology / Akrotiri Digs. [Online] Available at: https://www.santorini.com/archaeology/akrotiri.htm

By Ḏḥwty

http://www.ancient-origins.net

Greek gods

Mystery deepens over ancient tomb

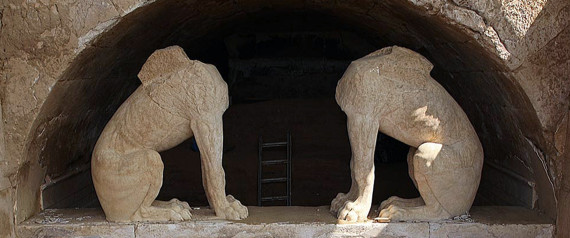

Geologist Evangelos Kambouroglou added that the mound inside which the rooms and the tomb were found is not man-made, as archaeologists had assumed, but a natural hill.

He also said that the Lion of Amphipolis, a huge 4th century BC sculpture of a lion on a pedestal, which is more than 25 feet tall, was too heavy to have stood at the top of the tomb, as archaeologists had claimed.

“The walls (of the tomb structure) can barely withstand half a tonne, not 1,500 tonnes that the Lion sculpture is estimated to weigh,” Mr Kambouroglou said.

As for the box-like tomb that contained the remnants of five bodies, possibly more, “it is posterior to the main burial monument … the main tomb has been destroyed by looters, who left nothing,” said Mr Kambouroglou.

“The marble doors (of the monument) contain signs of heavy use, which means many visitors came and went.”

Open Gallery 1

Open Gallery 1 Controversy surrounds the excavation of an ancient tomb in Greece which a leading archaeologist had suggested could be linked to the family of Alexander the Great.

The vaulted rooms had been dated to between 325 BC – two years before the death of ancient Greek warrior-king Alexander the Great – and 300 BC, although some archaeologists had claimed a later date.

Katerina Peristeri, the chief archaeologist in the recent excavation, had advanced the theory that a member of Alexander’s family, or one of his generals, could be buried in the tomb.

But the discovery of the boxy grave and the five bodies cast doubt on that theory, and Mr Kambouroglou’s announcement appears to disprove it entirely. Some archaeologists present during the announcement criticised Ms Peristeri’s absence and her methods.

Alexander, who built an empire stretching from modern Greece to India, died in Babylon and was buried in the city of Alexandria, which he founded. The precise location of his tomb is one of the biggest mysteries of archaeology.

His generals fought over the empire for years, during wars in which Alexander’s mother, widow, son and half-brother were all murdered – most near Amphipolis.

Press Association

http://www.independent.ie

Mystery Of Amphipolis Tomb Deepens With New Finding

Geologist Evangelos Kambouroglou also said Saturday that the mound inside which the rooms and the tomb were found is not man-made, as archaeologists had assumed, but a natural hill.

He also said that the Lion of Amphipolis, a huge sculpture of a lion on a pedestal , which is more than 25 feet (7.5 meters) tall, was too heavy to have stood at the top of the tomb, as archaeologists had claimed.

“The walls (of the tomb structure) can barely withstand half a ton, not 1,500 tons that the Lion sculpture is estimated to weigh,” Kambouroglou said.

As for the box-like tomb that contained the remnants of five bodies, possibly more, “it is posterior to the main burial monument … the main tomb has been destroyed by looters, who left nothing,” said Kambouroglou. “The marble doors (of the monument) contain signs of heavy use, which means many visitors came and went.”

The vaulted rooms had been dated to between 325 B.C. — two years before the death of ancient Greek warrior-king Alexander the Great — and 300 B.C., although some archaeologists had claimed a later date.

Katerina Peristeri, the chief archaeologist in the recent excavation, had advanced the theory that a member of Alexander’s family, or one of his generals, could be buried in the tomb. But the discovery of the boxy grave and the five bodies cast doubt on that theory and Kambouroglou’s announcement appears to disprove it entirely. Some archaeologists present during Saturday’s announcement criticized Peristeri’s absence and her methods.

Alexander, who built an empire stretching from modern Greece to India, died in Babylon and was buried in the city of Alexandria, which he founded. The precise location of his tomb is one of the biggest mysteries of archaeology.

His generals fought over the empire for years, during wars in which Alexander’s mother, widow, son and half-brother were all murdered — most near Amphipolis.

Costas Kantouris on twitter: @CostasKantouris

http://www.huffingtonpost.com

Alexander the Great Timeline

Peristeri on Amphipolis: The skeletons may be remnants of sacrifices or looters

By Spiros Sideris

By Spiros Sideris

“We need to focus on the monument, not the bones, which for me do not mean a lot. You cannot perform datings from the dead. For me the skeletons are meaningless. They mislead the investigation”.

These are the statements of the head of the excavation team at Amphipolis, Katerina Peristeri, in an interview with the Real News. Indeed, she goes even further saying that “for me issue of the ‘skeletons’ does not say anything. The area was so disturbed that you cannot draw clear conclusions. The robbers had ravaged everything. Because, as you can see, the burial chamber where they were looking for great treasures sustained a lot of damage, an enormous destruction”.

As for who the skeletons belong to, she was said: “There are many assumptions we can make. The skeletons may have been remnants of sacrifices, may even belong to the looters. Besides, the skeletal material was not in one place”.

Referring to the main dead she said: “Who is the main dead? There is a large piece of skeletal material from the dead found lower than the rest, ie close to the floor, and belongs to a short man, 1.60m. Even this skeleton, however, was scrambled by the robbers. And there is the other thing, if indeed the dead was so precious, they may had even taken him”.

In the same interview Katerina Peristeri speaks for all the other issues that have arisen: answers to her critics, expresses bitterness, describes her feelings for the blows she received, while she talks in detail about the “unique burial complex”, making extensive reference to the first phase of excavation and what comes next

– See more at: http://www.balkaneu.com/peristeri-amphipolis-skeletons-remnants-sacrifices-looters/#sthash.FfRdVrIZ.dpuf

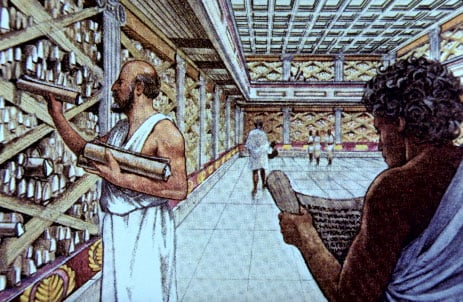

The destruction of the Great Library of Alexandria

Alexandria, one of the greatest cities of the ancient world, was founded by Alexander the Great after his conquest of Egypt in 332 BC. After the death of Alexander in Babylon in 323 BC, Egypt fell to the lot of one of his lieutenants, Ptolemy. It was under Ptolemy that the newly-founded Alexandria came to replace the ancient city of Memphis as the capital of Egypt. This marked the beginning of the rise of Alexandria. Yet, no dynasty can survive for long without the support of their subjects, and the Ptolemies were keenly aware of this. Thus, the early Ptolemaic kings sought to legitimize their rule through a variety of ways, including assuming the role of pharaoh, founding the Graeco-Roman cult of Serapis, and becoming the patrons of scholarship and learning (a good way to show off one’s wealth, by the way). It was this patronage that resulted in the creation of the great Library of Alexandria by Ptolemy. Over the centuries, the Library of Alexandria was one of the largest and most significant libraries in the ancient world. The great thinkers of the age, scientists, mathematicians, poets from all civilizations came to study and exchange ideas. As many as 700,000 scrolls filled the shelves. However, in one of the greatest tragedies of the academic world, the Library became lost to history and scholars are still not able to agree on how it was destroyed.

An artist’s depiction of the Library of Alexandria. Image source.

Perhaps one of the most interesting accounts of its destruction comes from the accounts of the Roman writers. According to several authors, the Library of Alexandria was accidentally destroyed by Julius Caesar during the siege of Alexandria in 48 BC. Plutarch, for instance, provides this account:

when the enemy tried to cut off his (Julius Caesar’s) fleet, he was forced to repel the danger by using fire, and this spread from the dockyards and destroyed the great library.

(Plutarch, The Life of Julius Caesar, 49.6)

This account is dubious, however, as the Musaeum (or Mouseion) at Alexandria, which was right next to the library was unharmed, as it was mentioned by the geographer Strabo about 30 years after Caesar’s siege of Alexandria. Nevertheless, Strabo does not mention the Library of Alexandria itself, thereby supporting the claim that Caesar was responsible for burning it down. However, as the Library was attached to the Musaeum, and Strabo did mention the latter, it is possible that the library was still in existence during Strabo’s time. The omission of the library can perhaps be attributed either to the possibility that Strabo felt no need to mention the library, as he had already mentioned the Musaeum, or that the library was no longer the centre of scholarship that it once was (the idea of ‘budget cuts’ seems increasingly probable). In addition, it has been suggested that it was not the library, but the warehouses near the port, which stored manuscripts, that was destroyed by Caesar’s fire.

The second possible culprit would be the Christians of the 4th century AD. In 391 AD, the Emperor Theodosius issued a decree that officially outlawed pagan practices. Thus, the Serapeum or Temple of Serapis in Alexandria was destroyed. However, this was not the Library of Alexandria, or for that matter, a library of any sort. Furthermore, no ancient sources mention the destruction of any library at this time at all. Hence, there is no evidence that the Christians of the 4th century destroyed the Library of Alexandria.

The last possible perpetrator of this crime would be the Muslim Caliph, Omar. According to this story, a certain “John Grammaticus” (490–570) asks Amr, the victorious Muslim general, for the “books in the royal library.” Amr writes to the Omar for instructions and Omar replies: “If those books are in agreement with the Quran, we have no need of them; and if these are opposed to the Quran, destroy them.” There are at least two problems with this story. Firstly, there is no mention of any library, only books. Secondly, this was written by a Syrian Christian writer, and may have been invented to tarnish the image of Omar.

Unfortunately, archaeology has not been able to contribute much to this mystery. For a start, papyri have rarely been found in Alexandria, possibly due to the climatic condition, which is unfavourable for the preservation of organic material. Secondly, the remains of the Library of Alexandria itself have not been discovered. This is due to the fact that Alexandria is still inhabited by people today and only salvage excavations are allowed to be carried out by archaeologists.

While it may be convenient to blame one man or group of people for the destruction of what many consider to be the greatest library in the ancient world, it may be over-simplifying the matter. The library may not have gone up in flames at all, but rather could have been gradually abandoned over time. If the Library was created for the display of Ptolemaic wealth, then its decline could also have been linked to an economic decline. As Ptolemaic Egypt gradually declined over the centuries, this may have also had an effect on the state of the Library of Alexandria. If the Library did survive into the first few centuries AD, its golden days would have been in the past, as Rome became the new centre of the world.

Featured image: One of the theories suggests that Library of Alexandria was burned down. ‘The Burning of the Library of Alexandria’, by Hermann Goll (1876).

By Ḏḥwty

References

Empereur, J.-Y., 2008. The Destruction of the Library of Alexandria: An Archaeological Viewpoint. In: M. El-Abbadi & O. M. Fathallah, eds. What Happened to the Ancient Library of Alexandria?. Leiden; Boston: Brill, pp. 75-88.

Haughton, B., 2011. What Happened to the Great Library at Alexandria. [Online]

Available at: http://www.ancient.eu.com/article/207/

[Accessed 8 May 2014].

Newitz, A., 2013. The Great Library at Alexandria was Destroyed by Budget Cuts, Not Fire. [Online]

Available at: http://io9.com/the-great-library-at-alexandria-was-destroyed-by-budget-1442659066

[Accessed 8 May 2014].

Plutarch, Life of Julius Caesar,

[Perrin, B. (trans.), 1919. Plutarch’s Lives. London: William Heinemann.]

Wikipedia, 2014. Destructionn of the Library of Alexandria. [Online]

Available at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Destruction_of_the_Library_of_Alexandria

[Accessed 8 May 2014].